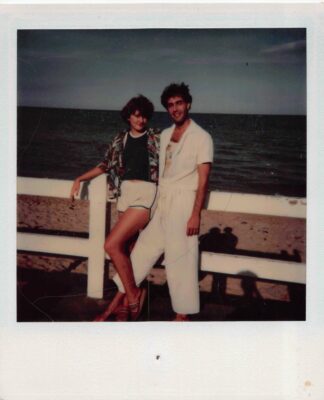

With Lenny Horowitz, South Beach, late 1970s

It was 1977. I didn’t think Barbara Capitman and Lenny Horowitz could throw a tea party much less transform the decrepit lower end of Miami Beach into the “Riviera of the South.” Through my flippant 21-year-old eyes it was where hippies went to score pot, the downtrodden bet on greyhounds, and old people sat on the porches of faded funny-looking apartment buildings waiting to die. Then there was Barbara and Lenny. She struck me as a frumpy Jewish middle-aged lady with a quavering voice and limp hair hanging in her face. He was just plain mad. A human amphetamine, his eyes bugged out when he was excited about something. That would be all the time. His brown curls had a mind of their own.

Quite the odd couple, they were two of the notable guiding lights of the Miami Design Preservation League that had formed the year before. Their team was on a mission to save the Art Deco buildings of South Beach and have a one square mile area listed on the National Register of Historic Places, protecting them from demolition. The once dazzling and unusual structures would sparkle again in newly painted pastels Lenny would oversee. They preached their gospel to anyone who would listen. They had even laid down in front of bulldozers to stop the destruction of some of them.

I found them mesmerizingly peculiar. Did I believe they would succeed? Nope.

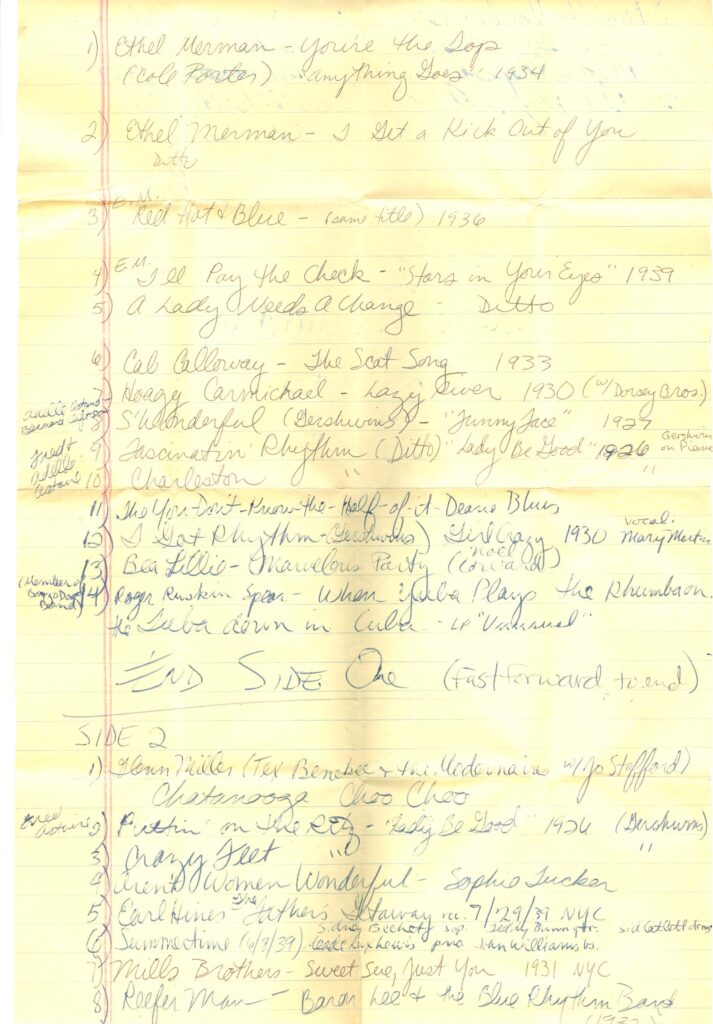

When MDPL put on a fundraiser, Lenny asked me to make a cassette tape of music they could play. I had a blast making a mix I still listen to.

Everyone had a glittering time though I don’t recall a lot of money was raised. Lenny was undaunted. “It’s only the beginning. Just watch.”

In 1979, the Miami Beach Architectural District was official. Okay, they accomplished that, I thought. The rest was surely pure pipe dream.

What has happened to South Beach—SoBe—is light years beyond the MDPL’s initial goal. Perhaps too much so. It is packed with trendy tourists year-round. The price of real estate is in the stratosphere. It’s as unrecognizable to me today as the rest of Miami, especially downtown. All that assures me I’m still in “The Fun and Sun Capital” of my youth is the 1925 Freedom Tower wedged between looming modern skyscrapers.

Lenny and Barbara proved me dead wrong and taught me a powerful lesson: never underestimate the power of passion. I could end the story there. But let me tell you how Lenny changed me.

THE DJ ORIGIN STORY

After my parents’ divorce in 1969, I spent my adolescence in Miami with my father and brother. I fell in love with radio in the early 1970s at what was then Miami-Dade Community College — even after being told by the student program director “Chicks can’t do Top 40 radio.” I finished my bachelor’s degree at Syracuse University majoring in Communications at the acclaimed Newhouse School. In my last semester I was program director at the school station, WAER. I clearly had gumption. In college. The real world was another matter.

You can take the girl out of Miami but you can’t take Miami out of the girl. It was so cold and gray in Syracuse I called it Zerocuse. The moment I graduated I fled back to Miami. My father had remarried in the interim. I found my own place that was in such a sketchy hood he installed bars on the widows of my first floor, roach-infested studio. The monthly rent was $135. I drove a used faded gold Pinto wagon to job interviews. I was sure my impressive degree would pay off quickly.

Lenny was my upstairs neighbor. I would hear him come home early in the morning after spending the night dancing in clubs and luxuriating at “the baths” with other gay men. I wasn’t sure how he paid his bills. He seemed to live off air and the kindness of strangers.

Our ten year age difference made no difference. We laughed, disco roller-skated, talked about everything and laughed some more. He introduced me to outrageous Neiman Marcus window designer Gaylord Cull. We figured out to have fun with very little money.

Cheap food and thrills with Lenny and Gaylord Cull. Gaylord would go on to be a renowned performance artist and painter.

Lenny steadfastly encouraged me in my lofty career pursuits as I hit up every radio station in town. My first choice was WSHE, the progressive rock station, hippie that I was. Two years before, when I attended Miami-Dade, I had written a report on the station and wrangled an interview with the male program director. I had asked him, since the announcers called the station SHE, had he considered a female DJ on the staff (hint, hint)? He told me studies had shown that men, their primary demographic, didn’t like the sound of the female voice on the radio because the frequency was too high. I had replied, “How would they know? They’ve never heard any.” He quickly ended the interview. I didn’t bother reaching out to them now for another reason. They already had their token female DJ on the late night shift.

Why the turnaround? There was a lot of pressure on radio stations at this time from feminists to put women on the air or risk having issues at license renewal time. There still were no females on Y-100 and 96X, the top hit music stations. They were in a hell of a dogfight that led to sensational radio. You could smell the testosterone coming out of the car speakers. I couldn’t imagine a woman on their airwaves, or even working behind the scenes. They had to be sexist snake pits.

The male program directors at the other stations, rock and middle-of-the-road formats, were happy to meet me. Many said, “We have no openings, but would you like to have dinner?”

Finally, I landed a part-time job at Record Land by the 163rd Street Mall. I was paid minimum wage ($2.30 an hour). It crushed my well-educated ego (what had my dad spent on tuition?) but I figured it kept me in touch with music. It was eye-opening to see what the public bought after I’d been in the ivory tower of free-form college radio. What sold were Barbra Streisand and disco hits. Van McCoy’s “The Hustle” led the pack.

I often sunk into a deep funk. Lenny never stopped pumping me up. “You’re going to be huge! Just watch!”

THE BIG BREAK

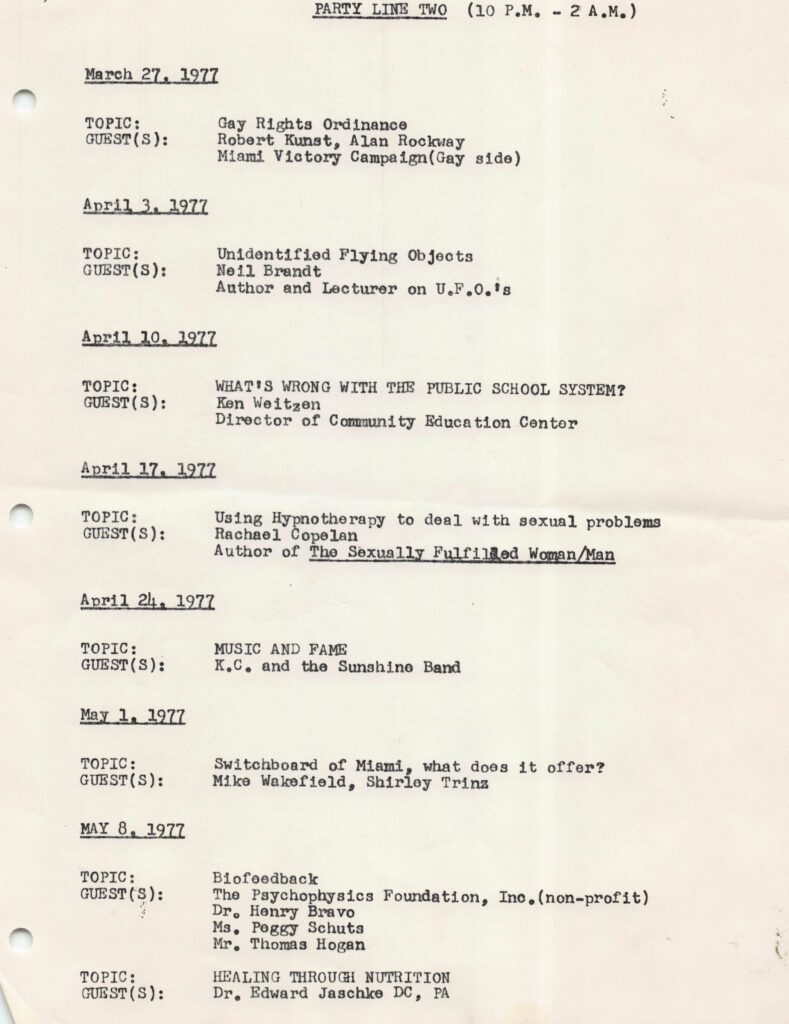

There was a woman at Record Land who talked to the music directors at local radio stations about what was selling. This was before SoundScan computerized record sales (that is, legitimized them and curtailed pay-offs to everyone in the music food chain.) She mentioned me to someone at 96X. I was dumbfounded when they hired me at $25 a week to host “Party Line,” a public affairs show that aired live late on Sunday nights. Twenty-one-year-old me was responsible for making sure they kept their license by covering topics relevant to their listeners. I tried to make it interesting. I brought in guests who talked about gay rights, the public school system, solar energy, UFOs. How that last one and few others like “Using hypnotherapy for sexual problems” and “Star Trek and Trekkies” related to public affairs I don’t know.

“See!” Lenny screamed. “You’re working at 96X!!!”

“For twenty-five dollars a week in the middle of the night on Sundays.”

“Your foot is in the door. Just watch. Now, when can you have me on to talk about MDPL?”

“Lenny, I’d love to, but we’d be laughing so hard I’ll be fired.” I promised to work him in when I was on firmer footing there.

Somehow, I managed to get KC and members of the Sunshine Band to agree to talk about “Music and Fame.” I didn’t run it by my boss until I was sure KC would agree. I figured it was a long shot and didn’t want anyone to see me fail in my mission.

Lenny was ecstatic. “They have to make you full-time after this!”

That’s exactly what I thought was going to happen when my boss called me to his office. Instead, he was mad. Because KC was now doing 96X a favor—and in the middle of the night, no less — they didn’t have to appear when the station really needed them, in drive time (morning and afternoon commutes). It was a win for Y-100. Oops.

Sample of 96X Party Line public affairs show topics. It aired live with callers Sunday nights from 10pm to 2am.

When the 96X receptionist position opened, I applied. Surely, I could do that. I was told I was over-qualified. Of course, I had mentioned my degree and P.D. position on my resume. When the program director made his assistant their first female DJ and put her on the overnight shift, I was gutted.

Sobbing to Lenny about how I was going nowhere fast, he said, “You belong on Y-100 anyway. It’s the better station. 96X will be kicking themselves in the ass. Just watch. And maybe you shouldn’t mention your degree and all that. These guys don’t have degrees, do they? They’re intimidated.”

He didn’t get it, I thought, how hard it was to break down doors in the #11 market in America when I only had college radio experience. I had no airchecks of me doing anything close to Top 40 radio. I had to use whatever ammo I had. I thought a degree meant something.

I tried to get an interview at Y-100. No one returned my calls.

“Send Tanner a tape of your answering machine messages,” Lenny suggested. “They’re brilliant!”

Creative, yes. Brilliant? Hardly. I had 20 seconds to relay in a creative way to leave a message. Twenty seconds is a long time to wait for a beep when all you want to say is “Call me back.” On one, I had ominous drums playing in the background as I was about to be eaten by cannibals. Another I was at a luau with Hawaiian music accompanying me.

I used the 96X studio to transfer the messages to a reel-to-reel tape, put it inside a box of assorted candies, gift-wrapped the box with colorful polka-dotted paper, and on the outside taped a postcard from Monkey Jungle with two chimps gazing at each other. On the back I wrote to Bill Tanner, program director and star of Tanner-in-the-Morning: “There’s more here than meets the eye.”

On August 3, 1977, I drove to the studio in Hollywood, just south of Ft. Lauderdale. I sat in my Pinto wagon and listened to a promo where a deep male voice said “We’re going balls out for Peter Frampton.”

Y-100 was releasing 10,000 ping pong balls on the beach that weekend. If you found one with those words on it you won tickets to the sold-out concert. (Good luck trying that today.)

As if a woman could say “balls out” on the air and not sound like an idiot. Luckily, it happened to be Y-100’s fourth birthday. My gift wouldn’t look suspicious.

The lobby was like a disco. Flashing lights around the ceiling. Leather built-in seats. Hit songs thumping through the speakers. I nervously left my gift with the receptionist and skedaddled.

Bill Tanner called me the next day.

He asked if I’d ever written commercials. Heart pounding, I said I’d written public service announcements, and I’d give it a shot. I said nothing about my degree or college radio experience. (Please don’t read this as I wasted my time and father’s money getting a degree. My college years allowed me to make mistakes, build my knowledge of the medium, and gain experience. If success = preparation + opportunity, I was prepared.)

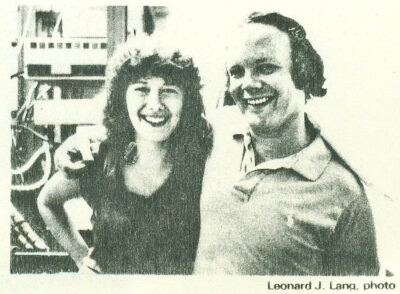

Bill Tanner reminded me of Ben Franklin. A little overweight, wire-rimmed glasses, brown hair that was thin on top and longer on the sides. He had an avuncular quality and laughed at my jokes. I somehow knew he would not be asking me to dinner, which put me at ease.

He gave me background on three businesses they were trying to woo and asked me to write a spot for each one. It turned out I had a gift for writing commercials. A week before my 22nd birthday I was hired at minimum wage (still $2.30).

With Bill Tanner-in-the-Morning, program director and morning star of Y-100 and my mentor.

Lenny went berserk. So did I.

On August 21, 1977, as Vice President of MDPL, Lenny was the guest for my last Party Line: “History of the City of Miami.” We laughed a lot and I didn’t care.

THE Y-100 ASCENT

Naturally, I wrote commercial scripts that needed a female voice. My female voice. Within two months I was named “The Y-onic Woman” and given a ridiculous costume to wear as I spotted bumper stickers all over South Florida. I gave away thousand-dollar bills, a speed boat, and a Silver Cloud Rolls Royce. People asked for my autograph. I had stalkers.

“What did I tell you!” cried Lenny. “What. Did. I. Tell. You.”

Lenny had moved out of our building and was living on South Beach. I moved into his apartment so I could enjoy the pastel, modular design he had painted on the wall. He called it Architectonics. “These are the colors you’re going to see all over South Beach,” he said.

Technically, they were not the original colors of the buildings. They had more punch, like colors of ice cream, and were irresistible.

Lenny Horowitz’s mural in his apartment on NE 33rd street, Miami.

By the end of 1977, as the songs from Saturday Night Fever climbed the charts, I was made Y-100’s first female DJ. My air name was “The Midnight Madame” then “The Madame” when they switched me to middays. Tanner wanted me to have a “real” air name. Some listeners had complained about “The Madame.” I liked the name because it was obviously made-up and allowed me to be another person. It was “The Madame” talking, not me. There was already a JoJo Kinkaid on Y-100. Anything with “Jo” was out. A fake real name—or was it a real fake name?—like Tanya or Kelly, seemed weirder to use than The Madame.

Lenny and I brainstormed. After rejecting scores of names, Shelley was tossed into the mix. “Shells. Beach. Florida!” he said. “I can see your publicity photos. A bikini top made of two big shells!”

I was relieved the photo never happened and I never liked Shelly. I rarely used it.

Middays on Y-100 as “The Madame”

I would go on to interview the Bee Gees, Michael Jackson, Bob Marley, and many more. On Valentine’s Day 1979, I interviewed Miami singer Bobby Caldwell whose hit “What You Won’t Do For Love” had entered the Billboard Top Ten. Y-100 was giving away heart-shaped, red vinyl copies of the single. Within a few months we were engaged. (We lasted five years. That’s another story.)

In the early 80s, 96X lost their broadcast license for various shenanigans, making way for a new hit station to take on Y-100: I-95FM. Soon I was hosting “Up and at ‘em with The Madame,” the first woman to hold that slot in South Florida radio. I didn’t last long before gravel-voiced Don Cox—famous for giving away “Cox Suckers” to his fans and various shenanigans involving drugs, drinking, and the law—replaced me.

WKTU in New York City, the number one market, snapped me up. I stayed in the Big Apple for almost 20 years, ending my radio career in 2003 as a DJ on Z100, America’s most-listened to music radio station.

I owe so much to Lenny Horowitz.

Whenever I’m in South Florida I make a pilgrimage to 11th street and Ocean Drive and gaze at the street sign that says: LEONARD HOROWITZ PLACE. Close by is another one named after Barbara Capitman.

I’ve since read online that his father cut off financial support to him because he was gay. I don’t recall him talking about his dad, as I didn’t talk about my mother who lived far away. Lenny and I visited his wonderful mom on Miami Beach a few times. I wonder if Lenny’s father lived long enough to see his son’s success. Did they reconcile, as I did with my mother at the end of her life?

Lenny died of AIDS in May of 1989. On March 10, 1990, his street on South Beach was official. I hope he knew it was going to happen and that it would be by the Versace mansion. He would have loved it. But what I think about most when I see it, besides Lenny, is this:

The power of passion.

Leonard Horowitz Place, South Beach