“Something went terribly wrong,” the stranger said. “Katie’s been in the hospital since her operation last month. She wanted me to call you. She’s on a ventilator and can’t speak.”

Katie was my father’s widow. After George Weitz died in 1985 at age 75, the British Katie, almost two decades his junior and not prone to extravagance, inherited all he had to give and became obsessed with ballroom dancing. To me, she was quite a jolly hoot and had made my father very happy. She deserved to live it up. He had done plenty for his children when he was alive and had told us not to expect anything when he passed. Neither did I expect her to turn his office in their Miami, Florida, home into a dressing room and fill it with custom-made outlandish outfits. One, I swear, had a string of lights sewn into it. She also enclosed their carport and transformed it into a dance studio with floor-to-ceiling mirrors reflecting a large mirrored ball hanging in the middle. When she had one leg amputated from the knee down, she kept whirling “on me peg leg” and winning competitions near and far.

How could I not admire her? I wouldn’t say I was like a daughter to the childless Katie, but we were certainly kind- red spirits who always got along and stayed in touch. I now resided in North Carolina.

She still lived alone in the house she had shared with my father and had told me she was about to have “a minor procedure” on her lung. She was 83. No procedure is minor at 83. She assured me she would fine. I had called to check in on her and no one picked up.

It was now Christmastime 2010. I rushed down to Miami after receiving the news that Katie was far from fine and stayed with one of her neighbors. Her house was already occupied by the person who had called me and was in charge of this ghastly situation.

Other than the accommodations made for her dancing, all seemed unchanged from when my father was alive. At first glance, the small one-story home seemed rather conventional. Details told another story: in the living room there was a swag lamp of a nude woman who looked like she was bathing in a waterfall; in the guest bathroom hung a framed print of a little girl studying a little boy urinating on a tree and thinking “Ce que c’est pratique!”; on a shelf filled with knickknacks were two rutting polar bears made of ivory that my father had acquired when we lived in Alaska.

Katie had already given me another Alaskan artifact: the bone from a whale’s willy. It looks like a 20-inch piece of driftwood and can double as a weapon. There had been many giggles when she passed it on to me as if it were King Arthur’s magical Excalibur.

She put up quite a fight in the hospital, certain she was heading back home. I eventually left. Her condition dragged on for several weeks. On my second visit, she was gone.

When I arrived for her memorial service, I was told she had willed me something. Really? What could it be?

The ballroom gown of my choice. Wow. Gown.

I took a closer look at them. I could feel the spirit of Carmen Miranda channeled into the thousands of sequins, yards of marabou and color-coordinated lamés. The shoes were equally over-the-top. I wouldn’t have blinked an eye if I’d found a pair with fish swimming in their Lucite heels. I had once called myself “The Rock and Roll Madame” on the radio in New York City and worn cascading wigs, flashy boots and miniskirts, and a gold diamond-studded finger- nail. There wasn’t a single gown I could see myself wearing. I picked the least flamboyant one.

I was also given the “Ce que c’est pratique!” print I had long admired.

Then the executor asked, “Would you like your father’s papers?”

“Papers?”

What papers? I wondered. I figured his things vanished long ago.

Then I saw it. Hiding behind the ballroom gowns all these years was an old green metal filing cabinet.

Upon a brief inspection, it was filled with files and photos pertaining to my father’s careers in the military and aviation. My surviving brother would find it interesting, I thought. Perhaps a scholar or enthusiast would, too, maybe. I packed up most of it and mailed it to my home.

Later, I unexpectedly received a huge box containing the majority of the ballroom gowns and Katie’s modest wedding rings from my father. I sold the rings and a couple of gowns (not much interest in them in the consignment world) and nearly recouped my Miami travel expenses. The rest of the gowns were donated to the Guilford Green Foundation, a Greensboro, North Carolina, charity that stages fabulous drag queen bingo fundraisers.

Katie now rests for all eternity with my father at Arlington National Cemetery, one of the highest honors a civilian can have. After unearthing their tender love notes, it’s clear they truly loved each other and deserved to be reunited.

If only I had found similar evidence between my father and my mother.

I thought that was the end of my thinking about Katie.

It took many years to bring myself to look at the contents of the old green metal filing cabinet.

When my mother was alive, her hoarding had reached such harrowing proportions that the fire department deemed her house uninhabitable. After the initial massive purge, the downsizing of her stuff and mine had continued over ten years. On and on and on went the gifts to friends and family—and the trips to Goodwill, consignment stores, and the post office to send out items sold over the Internet. Another box of stuff to go through was the last thing I wanted to face.

Then I pulled out a file and began skimming a story typed on thin onionskin paper.

Well, seems like one of the JN’s cracked a landing gear and Jim haywired the rig back in shape. So old Cap Yates shot the fever to our hero and it was all over by the time you could say G.I. Program.

From that day on Purdy just quit the profitable business of cultivator repairs and became one of the ill-nourished gentry that help put you and me in the business.

Who wrote this, Mark Twain? Whoever it was sure could turn a phrase. Had I not found the next item, I would have closed the box and, most likely, left it for that rainy day that would never come.

It was a letter dated January 16, 1947, from the editor of Aviation Maintenance & Operations magazine. Their office was in midtown Manhattan. The letter said my father’s Designated Aircraft Maintenance Inspector article would appear in their March issue. They would like it to be the first in a series, in every issue.

“The ‘crackerbarrel’ style is tops,” the editor wrote. “Looking forward to future ‘bang-up’ articles.”

A literary agent once told me, “It’s easier to get a book deal than to get an article placed in a magazine. And it’s nearly impossible to get a book deal.” From my own experience as a writer, I would agree. My dad was asked to write one for every issue of a major publication? True, it was a trade publication. Still, I was impressed.

My interest soaring, I went back to the one I’d started to read.

Well, in five hard years of what the ads say is “pleasant, dignified work,” Jim Purdy was second to none at twirling the old wire wrench and making the ornery OX’s quit misbehaving. He also learned to straighten Curtiss Reed props over a tree stump with a 10-pound sledge, bugger Model T nuts and bolts to fit a Hisso and all manner of neat little tricks of the trade for those days.

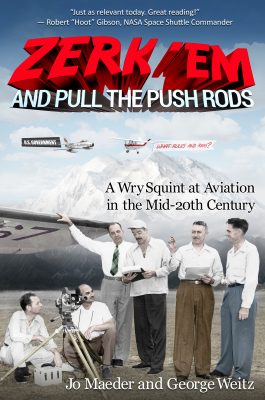

1928 found old Jim a name to be reckoned with in the manly art of zerk ’em and pull the push rods.

I was hooked.

I found 22 Inspector pieces. Where did this “crackerbarrel” style come from? He’d grown up on the tough streets of Brooklyn, not Mayberry!

Though I was blissfully ignorant of aviation beyond being a passenger, it didn’t impact my enjoyment of what my father wrote. I laughed often as I read his Inspector articles, bursting with pride and astonishment.

I also felt sad.

A memory surfaced of him telling me, offhandedly it seemed at the time, that he wished he had become a journalist. He said this when I’d fallen in love with one, the Miami Herald columnist (later with the New York Daily News), Jay Maeder. He effortlessly won my father’s approval. I didn’t think his regret over not becoming a journalist amounted to much, but by the time I discovered these papers, I had become a writer and knew the scale of effort that had gone into them.

Something told me I had struck a mother lode. But of what?

Click here to order

My curiosity in overdrive, I learned that by the end of 1946, right after World War II, close to 300,000 pilots and 40,000 registered aircraft in the United States quickly jumped to 400,000 and 85,000, respectively. You can imagine the headaches and hazards that created.

(I’d also never before truly wrapped my head around how quickly aviation grew after the Wright brothers first powered flight at the end of 1903. Ten years later planes were being used in World War I. That, to me, was like going from the first telephone to cell phones in a decade but even more mind-boggling. We’re talking about massive machines flying with people in them.)

A pilot friend told me there was one outfit, Bonanza, that boasted in the 1940s they could train anyone to fly a Beechcraft Model A-35 in 12 hours. “You need about a hundred hours to fly that plane. Fifty minimum,” he said. “They called it the ‘V-tail doctor killer,’ blaming the unusual shape of the tail that made it go faster. The real reason for all the crashes was that the pilots didn’t have enough training.”

My father’s career had started in airplane hangars on Long Island, New York, in the late 1920s when he was a teen. He knew Charles Lindbergh and worked on Amelia Earhart’s Lockheed Model 10 Electra. At one point he was flown to Saipan to identify wreckage that was thought to be her plane after she disappeared in 1937. It was the same kind of plane, he said, but whether it was hers he wasn’t sure. He eventually held a high position in the Federal Aviation Administration: Chief, Maintenance Division. He was responsible for programs involving the safety and reliability of all civil aircraft (non-military airplanes, private and commercial) in the United States. In 1962 he was the first government employee to receive the NATA Annual Award (National Air Transportation Association).

Ultimately, his job proved so stressful, he requested a reassignment at his doctor’s urging. He had developed Type II diabetes and cardiology issues. He retired the next year, in 1968, at age 58.

In the Alexandria, Virginia, house where we lived in the early 1960s, there was a large framed organizational chart in our den showing the headshots of everyone in my father’s FAA division. All men, of course. He was at the top, by himself. Underneath him, the rest of his team dutifully smiled for the camera. It conveyed instantly how important he was. But where did that framed chart go? I never saw it again. Did he find it embarrassing to tout his authority? Or was it a Pyrrhic victory and he needed no reminders. His stellar career had left him unhealthy and, soon, heading into his third divorce.

I knew little of what is in this book until I focused on the contents of that filing cabinet. That led to more archaeological digs: old audio interviews I’d never transcribed, government and military records I requested, photo albums I hadn’t looked at in decades, and conversations with my brother who was battling cancer. He was the last living person, other than myself, who knew my father well. Then I faced my own life-threatening medical crisis that, thankfully, resolved quickly. It was now or never to piece together the jigsaw puzzle of his life.

Previously, most of what I had learned about him were through family stories relayed to me by his sister, Julie Arden. We created a fierce bond when I was a teen, after my parents divorced. I also heard a few from my brother Art and much older half-brother George. But his career? I had never delved into it that much.

Until now.

After reading his many Inspector articles, I’m sure it was a deep regret, a grief even, that he stayed in his government job to provide for his family instead of becoming the writer he longed to be. Who knows what terrific stories were bubbling within, waiting to be banged out on an old Olivetti? He mentions one in the “Interviews” section of this book, a novel set in Haiti during the Banana Wars about “…the Blacks and the Marines…the love affairs.” He had served there when he was age 19 through 21.

I also came across two mentions of what a pain in the neck he thought writing was—the sign of a true writer! I’m sorry he isn’t here to see his name on the cover of a book as its author. It might have been his proudest achievement.

It was a mind-boggling revelation to see how much he had achieved—on his own—considering what a screw-up he’d been in his youth. He’d always been a mature, steady, rock of a father. Now I know it’s a miracle he lived as long as he did.

Two pieces of family lore were refuted by what I found: that my father had dropped out of high school at age 16 to join the Marines and that he was awarded two Purple Hearts—information that had been passed on to me by other family members. It turned out that, yes, he dropped out of high school at 16, but he went to work for aviation businesses. He earned his diploma at night school while working for them. He joined the Marines at 18. His mili- tary injury in 1929 that nearly killed him occurred before the first Purple Heart was awarded (1932). The second one was minor in comparison.

When I told Art there were no Purple Hearts in our father’s military records, he was as surprised as I, and said, “He told me he was just doing his job and didn’t deserve one. I guess I assumed he had them but wasn’t going to brag about it.”

This is how family mythologies are born.

When writing non-fiction, facts can often be fuzzy no matter how deeply you research. Everyone remembers things differently. Even things in writing can be contradictory. Emotional truth is key. That, I know, I have right.

As a child, my father was mostly a stranger to me. Every weekday morning as I was getting ready for school, he put on a suit and tie, picked up a hard black leather briefcase that opened and closed with a sharp snap, and headed out the door. He’d slip back in before Walter Cronkite delivered the news on TV. Then he’d read the newspaper, a Kent cigarette dangling from between his first two fingers, the ash steadily growing longer. Sometimes a shot of whiskey on the rocks was nearby. That was the extent of any drinking I saw, one tumbler barely filled.

I spent the night watching sitcoms that revolved around families I wished were my own. Even the Munsters showed love, affection and a sense of humor. My father stayed in his home office. On the weekend he’d sometimes make apple pancakes that were a real treat. He had a baked bean recipe that called for slow-cooking them for eight hours. My mother’s culinary offerings were extremely limited. I ate a lot of TV dinners, McDonald’s fries and Oreo cookies.

He traveled a lot for his FAA job. To him, the secret to world peace was for everyone to expose themselves to other cultures. If we did that, he said, “The less we see them as enemies.” This was from a man who had fought in the Banana Wars (Nicaragua and Haiti) and World War II, including the battles of Peleliu and Iwo Jima.

He often sent me postcards from exotic places like Lebanon, Turkey, France. One from Switzerland said: Arrived here this morning by train from Paris. The beds were small. Leaving tomorrow afternoon by train for Rome. Nice weather here. Love, Poppa. Occasionally he’d sign them with a drawing of a man with a mustache done with a few simple strokes. Other than that, the messages were bland. It was the thrill of getting a postcard, from my father, that excited this elementary school kid. It also put the travel bug in me. Often he’d bring back a doll. Once he gave me a child’s kimono, another time a grass skirt I could hula dance in. When I was a teen and passionate about playing the guitar and banjo, he went to Russia and brought back a balalaika.

Invariably, the moment he departed, some calamity would happen—like the washing machine going kaput— upsetting my mother. Upon his return, I remember no discussions about his trip, nor a warm welcome from “Mama Jo.” Any talk revolved around whatever went wrong while he was away.

I found more of his writings, including a detailed account of being part of an Alaskan team covering over 9,000 “last frontier” miles certificating bush pilots (referred to as non-scheduled operators) during a two-month period. One of the highlights: his incessant curiosity leading him to fall through the ice.

We lived in Anchorage from 1959 to 1961 when he was in charge of bringing the newly formed state’s flying community up to FAA standards. His description of flying in Alaska brought up crystal clear images in my pre-school memory bank.

The terrain from the mountains to the Arctic Ocean was nothing but a vast sea of snow and ice. Earth, sky and horizon all appeared the same and we felt as if we were flying inside a milk bottle whenever we gained altitude over 1,000 feet.

I found the start of a book on owning and operating a personal aircraft. He maintained an international consultant business for some time after leaving the FAA. His travels to Russia had the neighbors whispering that he was a spy.

Maybe he was.

If he could keep quiet about The Inspector, being matrilineally Jewish, and a marriage when he was young to a vaudeville actress many years his senior named Betty who rented a room from his parents (I was told by his sister Julie never to mention it)—I suppose he could hide anything.

From his outline for the book:

Public admiration growing by leaps and bounds, it is easy to understand that aviation held the biggest attraction for a segment of the population that was wild, unstable, and emotionally juvenile. What I’m getting at is that until the last 10 years or so, flying was not a business in the accepted sense but a sort of cult not unlike Hollywood swamis or numerologists. Through it all strode the ghosts of these hell-for-leather World War I pilots roistering their way through a leave in Paris.

Bless their souls, they started this business — but let’s let them lie peacefully along with General Custer and the U.S. Cavalry.

What happened to this book? Was no publisher immediately interested and he threw in the towel, or did he just lose steam once he retired? I do know that when the spirited, petite Katie entered his life right before I left for college, she became his primary focus. And vice versa. Having lost her first husband to illness, she was constantly worrying about my father’s health, admonishing him to eat less artery-clogging food and exercise more.

When my father walked me down the aisle at my wedding on Valentine’s Day 1985, he seemed shaky. He begged off joining our celebratory dinner that night.

I said to my new husband, “I have a terrible feeling I’ll never see him again.”

Jay answered, “That tough Marine will live forever.”

Two weeks later he died of a heart attack while vacationing in Portugal. I was 29. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors: 21-gun salute, caisson carrying a casket covered with an American flag and pulled by six white horses, and a big escort platoon band with two tubas. There were 75 perfectly attired, stone-faced personnel in all. So much pomp and circumstance.

Wait. The soldiers weren’t taking the casket off the caisson. They were opening the end of it. Someone reached inside. Out came a small stone box about the size of a toaster. A soldier spun on his shiny polished heel and effortlessly carried it away. It was one of those needle-across-the-record moments.

No casket?!

Shock replaced my grief. It seemed an indignant end, and I only knew the Cliffs Notes version of his life.

The box was placed on a pedestal with three soldiers on either side who performed a flawless routine, folding the flag into a tight triangle. It was handed to his grieving widow.

As my father’s cremains were placed inside an empty square hole in a wall with many other small sealed spaces, my shock turned to fury. It only subsided when I was told that this was his only option in order to be buried there. Now, it doesn’t matter. I’m over it. I’ve seen many loved ones reduced to small boxes, as I will one day be.

After his passing, an aviation newsletter paid tribute to him.

“George Weitz was one of the most important, dynamic and effective persons the FAA ever had in Washington Headquarters, where aviation maintenance is concerned. He brought about a complete change in the attitude of both the FAA and the industry in regard to the true value of the maintenance man. He helped raise their image above that of ‘just grease monkeys,’ to a position where their importance in the overall aviation safety effort was finally realized. All present FAA airworthiness inspectors can thank George Weitz for making it possible for them to enjoy the positions of respect held by them today, as can most of the Maintenance Technicians employed by industry at this time.”

I’d had no idea.

Sadly, Art passed away shortly before this book was published. My other brother George, from my father’s previous marriage, was an airplane mechanic who found he was happier running his own auto repair business. He died right before I received the call about Katie. He would have been a great resource, too. He was around age seven during The Inspector days. Did he read the columns? Did his mother?

I’ll never know.

What I do know is plenty. That old filing cabinet led to an exotic feast that would satisfy the appetite of any lover of aviation, dry wit and improbable success.

Shall we dig in?

THE AUTHORS, JO MAEDER and GEORGE WEITZ

Click here to order